UK faces tidal wave of plastic if ‘poorly designed’ Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) is adopted

- Plastic packaging would dominate supermarket shelves under flat rate DRS

- 60% of shoppers would switch from endlessly recyclable aluminium cans to plastic bottles

- Food and beverage waste would continue to rise unnecessarily

UK supermarket shelves could be awash with plastic packaging, replacing billions of endlessly recyclable beverage cans, if the UK adopts a flat rate deposit return scheme (DRS). That is the key finding from the Aluminium Packaging Recycling Organisation (Alupro), which has today (27 January) launched an extensive report analysing the implications of a poorly designed national scheme.

Developed in partnership with independent think-tank London Economics, alongside experts from across the UK packaging sector, the document analyses the environmental and economic implications of implementing a flat rate versus a variable rate deposit fee.

Aiming to tackle plastic pollution, increase recycling rates, improve recyclate quality and minimise litter, England, Wales and Northern Ireland’s long-awaited DRS is expected to come into force in 2023. The scheme will see a deposit value added to the price of a beverage product in store, which will be refunded to the customer when empty packaging is returned to a designated collection point.

While a variable rate fee would see containers allocated with a deposit value based on container size, a flat rate model would apply a fixed fee to all beverage containers. This unsophisticated approach could see customers charged an additional £4.80 for a 24-can multipack (on top of product purchase price) compared to just 80p for a 2 litre plastic bottle, which research suggests would result in 60% of shoppers opting for larger, cheaper, but much less sustainable plastic alternatives.

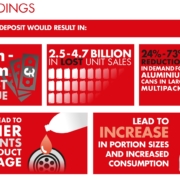

Alongside the price hikes and increase in plastic packaging, Alupro’s report uncovers a number of wider concerns posed by a flat rate model. Indeed, modelling suggests that a fixed fee model would result in 10% lower return volumes in total than a variable rate system. Conversely, a variable rate system would see the government achieve their 90% return rate almost a year earlier, leading to a higher recycling rate and less litter on the streets.

In addition, demand for aluminium cans – the world’s most widely recycled beverage container – would likely fall by c.11%, resulting in the industry being hit with an annual production shortfall of 4.7 billion units and the very real possibility of plant closures. With >75% of aluminium cans recycled every year, this would not only impact upon the UK’s national recycling rates, but also our thriving aluminium production industry.

Furthermore, with shoppers substituting convenient multipacks for cost-effective (but often impractical) large bulk containers, the UK could see a significant increase in portion sizes, or experience an immediate and unnecessary hike in product waste.

Rick Hindley, executive director at Alupro, commented: “While we are fully supportive of a well-designed DRS, research surrounding best practice design is limited. Our report aims to fill the gap and provide extensive modelling into the real-world implications of differing deposit fee options.

“While some may think that a flat rate deposit fee would be easier to implement, this isn’t necessarily the case. What’s more, it would result in a tidal wave of unnecessary plastic – a key issue that the scheme is fundamentally trying to solve. If the UK adopted a variable rate DRS, demand for plastic would drop notably. What’s more, we would see significantly higher return rates in the first two years of DRS operation and limited impact on portion size or product waste.

“Our concern is that simplicity will override sustainability in senior-level decision making. As such, we are imploring the government to take our statistics and modelling into close consideration when discussing the design of the UK’s DRS.”

ENDS